Written by Kieran Chalk

I. Introduction: From Philosophical Foundations to the Extended Mind with LLMs

The nature of the mind and its relationship to the physical world has long captivated philosophers, scientists, and thinkers across disciplines. The philosophy of mind delves into fundamental questions about consciousness, cognition, and the very essence of our subjective experiences.

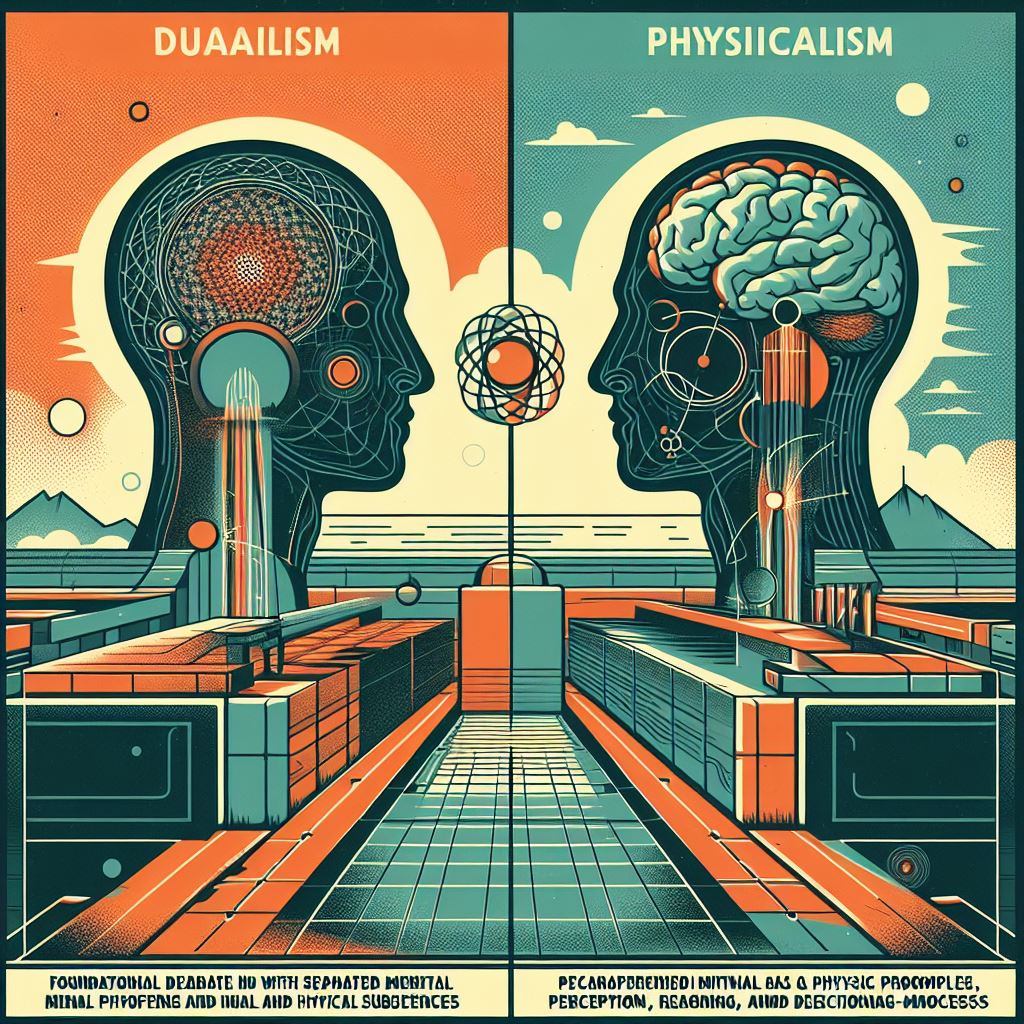

This exploration begins by laying out the foundational debates surrounding the mind-body problem, contrasting perspectives like dualism, which posits a separation between mental and physical substances, and physicalism, which asserts that mental phenomena are ultimately physical processes. It then examines how these viewpoints intersect with our understanding of cognition – the mental processes underlying perception, reasoning, decision-making, and other faculties.

Challenging traditional cognitivist models, the embodied, embedded, enactive, and extended (4E) cognition framework offers a holistic reconceptualization. It emphasizes the deeply intertwined nature of mind, body, and environment, proposing that cognitive processes are shaped by our physical embodiment, situatedness within contexts, active engagements with the world, and integration of external resources.

This philosophical backdrop sets the stage for grappling with the profound implications of recent technological developments, particularly large language models (LLMs) and their potential to become interactive components of our extended cognitive systems. If our minds can offload cognitive tasks onto external tools and artifacts, as the extended mind theory suggests, then LLMs – with their vast knowledge bases and advanced language processing capabilities – may play a transformative role in augmenting and shaping human cognition.

The following sections explore this notion, analysing the potential for LLMs to influence human thinking, the complex interplay of agency and responsibility within this extended cognitive system, and the emergent phenomena that arise from the integration of human and artificial components. As we venture deeper into this domain, key questions emerge: Who holds sway in these human-LLM interactions? How do we navigate the ethical implications of entangling our minds with powerful AI systems? And ultimately, what does it mean for us as conscious, thinking beings when the boundaries of our cognitive processes become permeable and intertwined with intelligent machines?

By grounding this inquiry in the rich tapestry of philosophical discourse on the mind, we can approach these questions with a deep appreciation for their profundity and a nuanced understanding of the stakes involved. The following sections offer a thought-provoking exploration of the intersections between philosophy, cognitive science, and cutting-edge technologies, inviting us to re-examine our conceptions of mind, cognition, and the nature of intelligence itself.

II. Unveiling the Mind: Core Topics in Philosophy of Mind

The philosophy of mind is a branch of philosophy that explores the nature of the mind, mental states, consciousness, and their relationship to the physical world. It is a highly complex and multifaceted field that has been studied and debated by philosophers, scientists, and thinkers for centuries. Here are some key aspects and topics within the philosophy of mind:

Mind-body problem: This central issue deals with the relationship between the mind (subjective conscious experience) and the body (physical material aspect).

Dualism: The view that mind and body are separate substances.

Physicalism: The view that the mind is a physical process.

Monism: The view that mind and body are different aspects of the same substance.

Consciousness: Consciousness, or subjective experience, is a puzzling phenomenon that philosophers of mind grapple with. Questions arise about the nature of consciousness, its relationship to the brain and physical processes, and whether it can be fully explained by scientific means.

Intentionality: Intentionality refers to the ability of the mind to represent or be directed toward objects, properties, or states of affairs. Philosophers examine how mental states like beliefs, desires, and thoughts can be about or represent things in the world.

Qualia: Qualia are the subjective, qualitative aspects of conscious experience, such as the reddish quality of seeing a red apple or the particular flavour of a wine. The existence and nature of qualia raise questions about the relationship between subjective experience and objective, physical processes.

Mental causation: This concerns the question of whether and how mental states can cause physical events or actions. It relates to the issue of free will and the causal efficacy of the mind in a physical world.

Artificial intelligence and the nature of mind: With the development of AI systems, questions arise about whether machines can truly have minds, consciousness, or intelligence in the same way that humans do. This touches on issues of functionalism, the Turing test, and the nature of cognition.

Personal identity: Philosophers explore questions of what constitutes personal identity over time, the role of memory and consciousness in personal identity, and the possibility of mind uploading or transhumanist scenarios.

The philosophy of mind draws upon various disciplines, including neuroscience, cognitive science, psychology, and computer science, as well as traditional philosophical methods of conceptual analysis, thought experiments, and logical reasoning. It remains a vibrant and actively debated field, with implications for our understanding of ourselves, our place in the world, and the nature of reality itself.

III. Delving Deeper: Dualism and the Mind-Body Problem

Dualism in the context of the philosophy of mind is a view that posits a clear distinction between the mind and the body, suggesting that they are two fundamentally different kinds of entities. This perspective is most famously associated with the 17th-century philosopher René Descartes, who argued that the mind is a non-physical substance that is distinct from the physical brain. Here’s a closer look at dualism:

Substance Dualism: This is the classic form of dualism, which holds that the mind and body are composed of different substances. The mind is thought to be immaterial and not subject to physical laws, while the body is material and operates within the physical realm.

Property Dualism: This form of dualism suggests that there are mental properties (like consciousness) that are not physical properties. Property dualists argue that while the brain is a physical substance, it has non-physical properties that cannot be explained by physical science alone.

Interactionism: This is a subtype of substance dualism that posits that the mind and body can causally interact with each other. For example, mental decisions can lead to physical actions, and physical sensations can lead to mental experiences.

Challenges to Dualism: Dualism faces several challenges, including the problem of mind-body interaction (how can a non-physical mind cause physical actions?), and the issue of parsimony (physicalism offers a simpler explanation by positing only one kind of substance).

Arguments for Dualism: Proponents of dualism often argue that there are aspects of human experience (like consciousness, intentionality, and qualia) that cannot be fully explained by physical processes alone. They may also appeal to intuitions about personal identity and the existence of free will.

Arguments against Dualism: Critics argue that dualism is inconsistent with our scientific understanding of the world. They point to the success of neuroscience in explaining mental processes and question how non-physical substances could interact with the physical brain.

Philosophical Implications: Dualism has significant implications for our understanding of personal identity, the nature of consciousness, and the possibility of life after death. It also raises questions about the nature of reality and our place within it.

In the philosophy of mind, dualism remains a compelling but controversial position. While it provides a framework for thinking about the unique qualities of mental experiences, it also faces significant philosophical and scientific challenges. The debate between dualism and monism, particularly physicalism, continues to be a central issue in the philosophy of mind.

IV. Physicalism: The Mind Explained by Matter

Physicalism, in the context of the philosophy of mind, is the view that everything that exists is physical or supervenes on the physical. In other words, it posits that all phenomena, including mental phenomena like thoughts, feelings, and consciousness, can be explained in terms of physical processes. Here’s an exploration of physicalism:

Monistic View: Physicalism is a monistic theory, which means it asserts that there is only one kind of substance in the universe – physical substance. This contrasts with dualism, which posits both physical and non-physical (mental) substances.

The Mind-Brain Identity Theory: One of the central claims of physicalism is that mental states are identical to brain states. For example, the experience of pain is nothing over and above the firing of certain neurons in the brain.

Functionalism: A related view within physicalism is functionalism, which suggests that mental states are defined by their functional roles – how they interact with other mental states and the body. According to functionalism, a mental state is akin to a role in a system, which could, in principle, be realized by non-biological entities like AI.

Eliminativism: Some physicalists adopt an eliminativist stance, arguing that common-sense psychological concepts like beliefs and desires don’t correspond to actual brain processes and should be eliminated in favour of more accurate neuroscientific descriptions.

Non-Reductive Physicalism: This perspective holds that while mental states are physical in nature, they cannot be reduced to brain states. Non-reductive physicalists argue that mental properties emerge from physical processes but have their own causal powers.

Challenges to Physicalism: Physicalism faces several challenges, such as explaining qualia – the subjective, experiential qualities of mental states. Critics argue that physical descriptions cannot capture the essence of what it’s like to have a particular experience.

Implications: The implications of physicalism are profound, affecting our understanding of consciousness, free will, and the nature of reality. If physicalism is true, it suggests that understanding the brain is key to understanding the mind.

Physicalism remains a dominant view in the philosophy of mind, largely due to its compatibility with the scientific worldview. However, it continues to be debated and refined as our understanding of both the brain and the mind evolves.

V. Unveiling Reality: A Deep Dive into Monism’s Many Forms

Monism in the philosophy of mind is the view that there is only one kind of substance or essence that constitutes reality, and this includes the mind. Unlike dualism, which posits both physical and non-physical substances, monism maintains that everything is fundamentally the same kind of thing. Here’s a deeper exploration of monism:

Material Monism (Physicalism): This is the belief that only physical things exist. According to this view, mental states are physical states, and consciousness and thought processes are ultimately physical processes occurring in the brain.

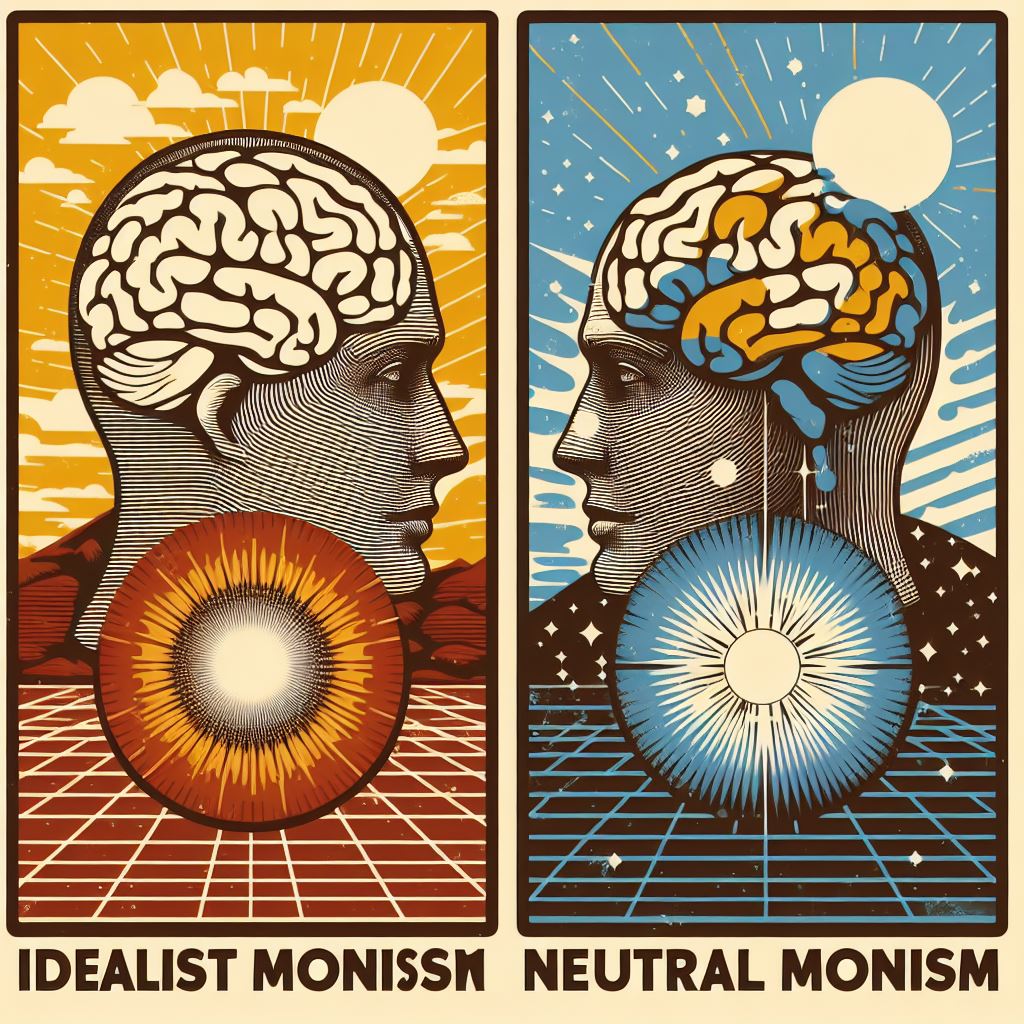

Idealism: This form of monism argues that only mental substances exist. The physical world, as we perceive it, is either a construction of the mind or an illusion. George Berkeley, an advocate of idealism, famously stated, “To be is to be perceived”.

Neutral Monism: This perspective suggests that the fundamental substance of the universe is neither mental nor physical but some third kind of substance that is ‘neutral.’ Both mental and physical properties can be seen as manifestations of this underlying substance.

Panpsychism: A variant of monism that posits that mind or a mind-like aspect is a fundamental and ubiquitous feature of the universe. It suggests that all matter has a mental aspect, although not all matter is conscious in the way humans are.

Anomalous Monism: Proposed by Donald Davidson, anomalous monism is a form of monism that holds that mental events are identical with physical events, and while mental properties cannot be reduced to physical properties, they are nonetheless dependent on them.

Monism challenges the traditional mind-body dualism by suggesting a more unified approach to understanding the nature of reality. It has various implications for our understanding of consciousness, the self, and how we relate to the world around us. Monism continues to be a significant and influential perspective in the philosophy of mind, offering a counterpoint to dualistic and reductionist views.

VI. The Mind at Work: Exploring Cognition through Philosophy

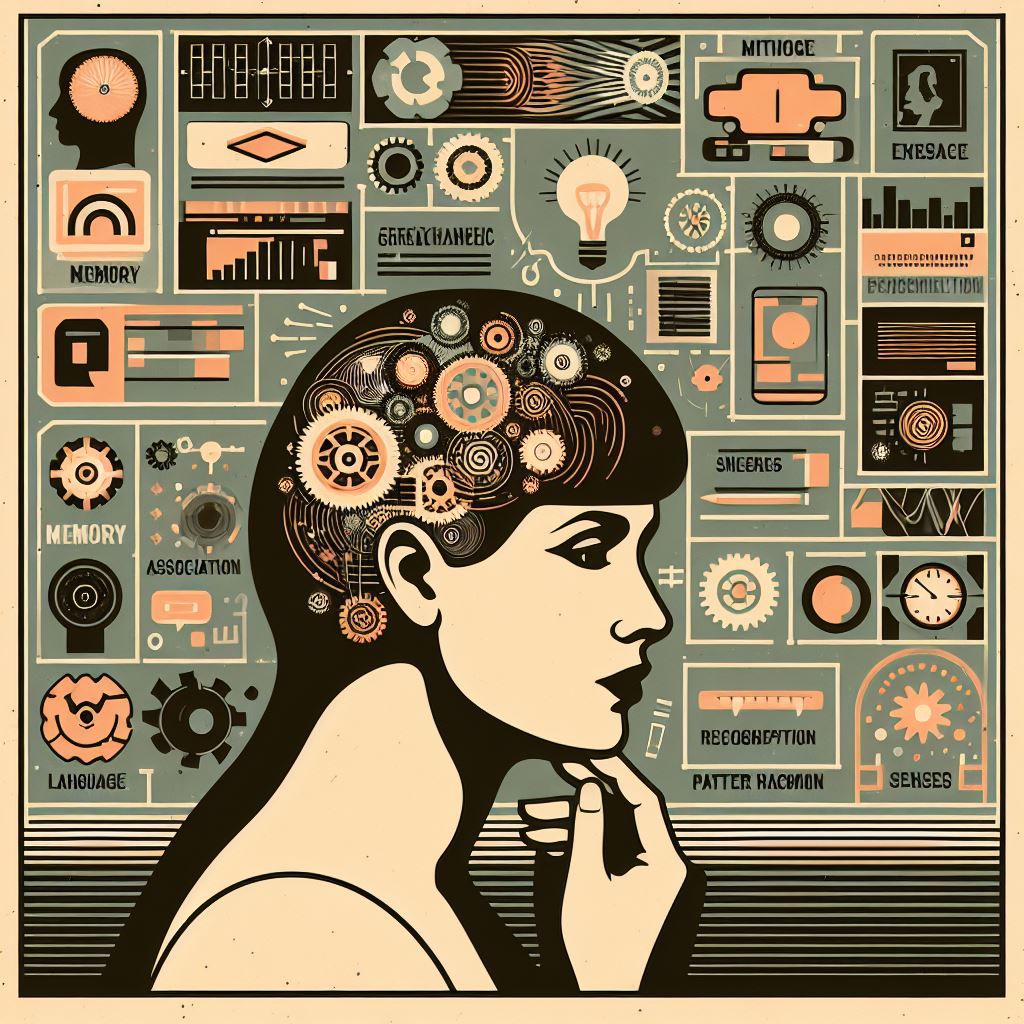

Cognition, broadly defined, is the mental action or process of acquiring knowledge and understanding through thought, experience, and the senses. It encompasses a wide range of mental faculties, including perception, attention, memory, reasoning, problem-solving, decision-making, and language.

The philosophy of mind, as it relates to cognition, explores the nature of these mental processes, their relationship to the physical brain and body, and the broader implications for our understanding of the human mind and consciousness.

Here are some key areas where the philosophy of mind intersects with the study of cognition:

Cognitive architecture: Philosophers investigate the fundamental structure and organization of cognitive processes. This includes questions about the modularity or unity of the mind, the nature of mental representations, and the role of innate versus learned cognitive faculties.

Consciousness and cognition: The relationship between conscious experience and cognitive processes is a central concern. Philosophers examine whether consciousness is necessary for cognition, the role of qualia in cognitive processes, and the possibility of unconscious or non-conscious cognition.

Mental representation and intentionality: Cognitive processes involve the representation and manipulation of information about the world. Philosophers explore the nature of these mental representations, their semantic content, and how they can be about or refer to external objects and states of affairs (intentionality).

Rationality and reasoning: The philosophy of mind investigates the nature of rational thought, the principles of logic and inference, and the cognitive processes underlying reasoning, decision-making, and problem-solving.

Language and cognition: The relationship between language and thought is a longstanding area of inquiry. Philosophers examine the cognitive underpinnings of language acquisition, the role of language in shaping thought, and the nature of linguistic representations in the mind.

Embodied cognition: This perspective challenges the traditional view of cognition as purely abstract and disembodied, emphasizing the role of the physical body, sensorimotor processes, and environmental interactions in shaping cognitive processes.

Artificial cognition: With the development of artificial intelligence and cognitive science, philosophers explore the possibility of machine cognition, the nature of computational models of cognition, and the implications for our understanding of the human mind.

The philosophy of mind, in its investigation of cognition, draws upon insights from psychology, neuroscience, linguistics, computer science, and other related fields. It aims to provide a conceptual framework for understanding the nature and mechanisms of cognitive processes, and their relationship to the broader philosophical questions about the mind, consciousness, and our place in the world.

VII. Distinguishing Cognition from Consciousness

While cognition and consciousness are intimately linked, they represent distinct aspects of the human mind. Understanding the difference between these two concepts is crucial for a comprehensive grasp of our mental life.

Cognition refers to the mental processes involved in acquiring knowledge and comprehension. These processes include thinking, knowing, remembering, judging, and problem-solving. Cognition is concerned with the mechanisms by which we understand and interact with the world. It is often studied objectively through observable behaviours and neural mechanisms.

Consciousness, on the other hand, is the subjective experience of the mind and the world. It encompasses our awareness of thoughts, feelings, and surroundings. Consciousness is what gives rise to the qualitative, first-person perspective of experiences, often referred to as qualia. It is the ‘what it is like’ aspect of mental states – the feeling of pain, the redness of red, or the taste of a fruit.

The primary difference lies in their accessibility:

Cognition can occur both consciously and unconsciously. For example, we can solve a problem or remember a fact without being acutely aware of the cognitive processes involved.

Consciousness is inherently tied to awareness. If a process or experience is not part of our awareness, it is not part of our conscious mind.

Another key distinction is their functionality:

Cognition is functional; it serves a purpose in our interaction with the environment. It allows us to process information, make decisions, and perform actions.

Consciousness does not necessarily have a clear functional purpose. Philosophers and scientists debate its role, with some arguing it is a by-product of complex cognition, while others believe it has evolved to provide an adaptive advantage.

The philosophical debate surrounding consciousness and cognition often centres on whether consciousness can be fully explained by cognitive processes. Some argue that consciousness is just another cognitive process, while others contend that it is a distinct phenomenon that cannot be reduced to neural activities or computational models.

In summary, cognition is the broad set of processes by which we come to know and interact with the world, while consciousness is the felt quality of experiences. The study of their interplay remains one of the most fascinating and challenging areas of philosophy and cognitive science, as it touches upon the very essence of what it means to be human. The ongoing exploration of this relationship promises to shed light on the intricate workings of the mind and the enigmatic nature of consciousness itself.

VIII. The Mind-Body Debate in Cognition: Dualism, Physicalism, and Monism

In the context of cognition, dualism, physicalism, and monism offer different perspectives on the relationship between the mind and the brain, and how cognitive processes occur. Here’s an exploration of each:

Dualism: In the realm of cognition, dualism posits that mental phenomena (like thoughts, beliefs, and desires) are fundamentally different from physical brain states. Cognitive processes, according to dualism, are not just the result of neural activity but involve a non-physical mind that interacts with the brain. This view raises questions about how non-physical mental events can cause physical actions, such as when deciding to move a hand.

Physicalism: Physicalism asserts that all cognitive processes are physical processes. This means that thoughts, feelings, and consciousness can be explained entirely by the workings of the nervous system and brain chemistry. From this perspective, understanding cognition requires a thorough understanding of the brain’s physical structure and function. Physicalism aligns with the scientific approach to studying cognition, which often involves looking for neural correlates of mental states.

Monism: Monism, in the context of cognition, can take several forms, but it generally holds that there is only one substance or essence to reality, which encompasses both the mind and the brain. Material monism, or physicalism, is one form, but there are also idealist and neutral monist positions. Idealist monism would argue that the physical brain and its processes are ultimately a manifestation of the mind, while neutral monism suggests that both mental and physical properties emerge from a more fundamental, neutral substance. These positions impact how we conceptualize cognition and its relation to the physical brain.

Each of these philosophical views has implications for cognitive science. Dualism suggests that there might be aspects of cognition that cannot be fully explained by physical science alone. Physicalism implies that advances in neuroscience will lead to a complete understanding of cognition. Monism opens up the possibility that cognition is a manifestation of a more fundamental reality that is neither purely physical nor purely mental.

Understanding these perspectives is crucial for anyone interested in the philosophy of mind and cognitive science, as they shape the questions we ask and the methods we use to explore the nature of thought, consciousness, and the self.

IX. Beyond the Brain: Embodied Cognition and the 4E Approach

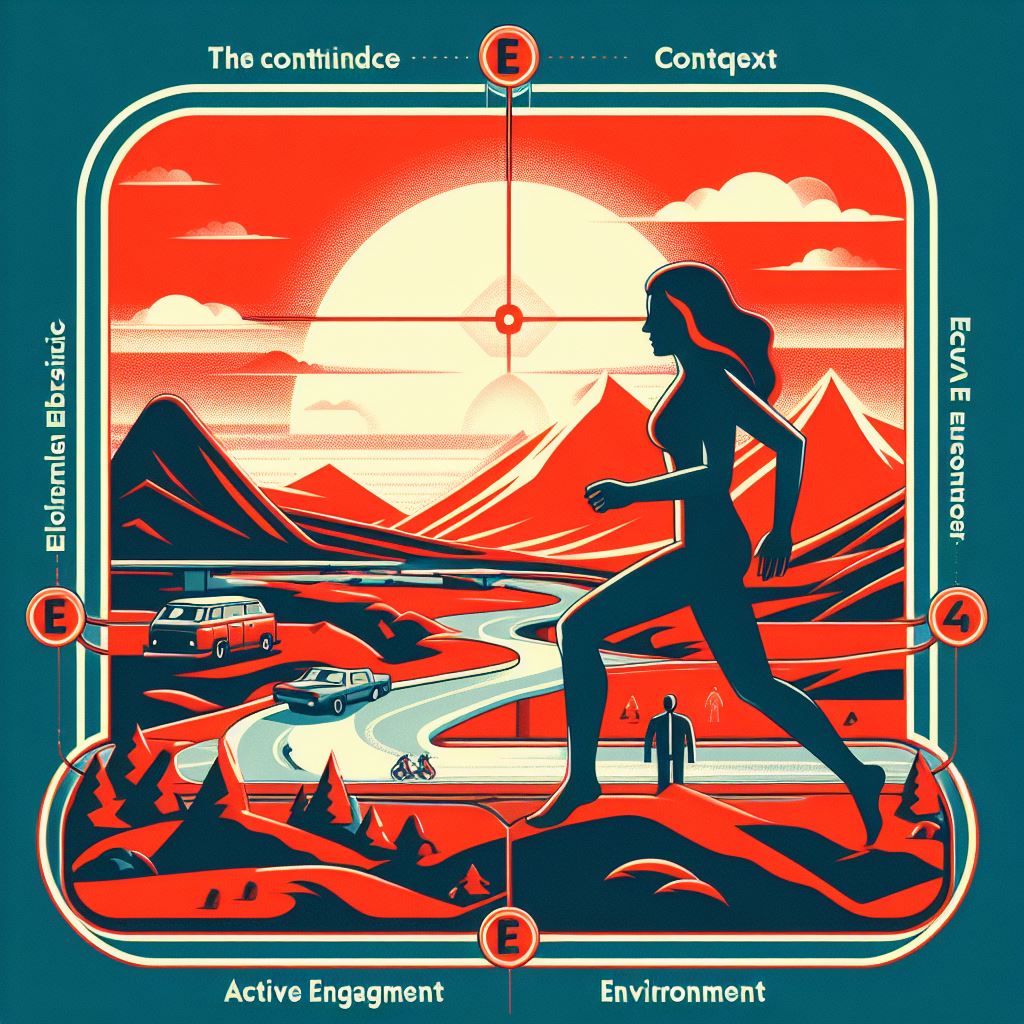

4E cognition, also known as the 4E approach or 4E cognition thesis, refers to a philosophical perspective that emphasizes the embodied, embedded, enactive, and extended nature of cognitive processes. It challenges the traditional view of cognition as a purely internal, disembodied process occurring solely within the brain. Here’s an explanation of each aspect of 4E cognition:

Embodied cognition: This aspect highlights the crucial role that the physical body plays in shaping cognitive processes. Our sensorimotor experiences, bodily interactions with the environment, and the constraints imposed by our physical form all influence how we perceive, think, and reason. Cognition is seen as grounded in the body’s interactions with the world, rather than being an abstract, disembodied process.

Embedded cognition: Cognitive processes are embedded within specific environmental and cultural contexts. Our cognition is shaped by the physical, social, and cultural environments in which we are situated. The environment is not just a passive backdrop but an active component that structures and shapes our cognitive activities.

Enactive cognition: This aspect emphasizes the dynamic, interactive nature of cognitive processes. Cognition is viewed as an active process of sense-making, where the mind and the world are coupled together in a continuous, reciprocal interaction. Cognition is not just a matter of representing or mirroring the world but actively constructing and enacting meaning through embodied action.

Extended cognition: The extended cognition thesis proposes that cognitive processes can extend beyond the boundaries of the individual brain and body, incorporating external resources and tools as part of the cognitive system. Our use of notebooks, calculators, smartphones, and other external artifacts can be seen as an extension of our cognitive abilities, blurring the lines between what is internal and external to the cognitive process.

The 4E cognition approach challenges the traditional computational and representational theories of mind, which viewed cognition as a series of internal, disembodied processes operating on abstract symbolic representations. Instead, 4E cognition emphasizes the deeply intertwined nature of mind, body, and environment, and the active, dynamic, and situated aspects of cognitive processes.

This perspective has gained traction in various fields, including philosophy of mind, cognitive science, artificial intelligence, and robotics. It has implications for our understanding of perception, memory, language, decision-making, and other cognitive faculties, as well as for designing intelligent systems that can effectively interact with and adapt to the real world.

Overall, 4E cognition provides a holistic and embodied view of cognitive processes, emphasizing the complex interplay between the mind, body, and environment in shaping our experiences and understanding of the world.

X. Bridging the Divide: 4E Cognition and Monism vs. Dualism and Physicalism

4E cognition relates most closely to monism, particularly to non-reductive physicalist and emergentist perspectives within monism. Here’s how 4E cognition aligns with these views:

Non-Reductive Physicalism: This form of monism suggests that while mental states are grounded in physical processes, they cannot be fully reduced to these processes. 4E cognition aligns with this view by suggesting that cognitive processes are not just brain processes but involve the body, the environment, and the interactions between them. It acknowledges the physical basis of cognition while also recognizing the complexity and irreducibility of cognitive phenomena.

Emergentism: Emergentism is a philosophical position within monism that posits that higher-level phenomena emerge from the complex interactions of lower-level processes. 4E cognition can be seen as an application of emergentism, where cognitive processes emerge from the dynamic interactions between an organism and its environment, not solely from neural activity.

4E cognition challenges the traditional internalist view of cognition that is often associated with dualism, which separates the mind from the physical world. Instead, 4E cognition emphasizes the continuity between the mind, body, and environment, which is more in line with monistic views that see mental and physical phenomena as aspects of the same reality.

In summary, 4E cognition is compatible with monistic views that emphasize the physicality of cognition while also recognizing the importance of the body and environment in cognitive processes. It moves beyond the mind-body dualism and supports a more integrated understanding of cognition as it occurs in real-world contexts.

However, 4E cognition offers a perspective on the mind that contrasts with both dualism and physicalism in interesting ways:

Relation to Dualism: Dualism posits that the mind and body are fundamentally different substances. 4E cognition challenges this by emphasizing the inseparability of the mind, body, and environment. It suggests that cognitive processes are not solely the product of an immaterial mind but arise from the dynamic interactions between our physical bodies and the physical world. Thus, 4E cognition tends to reject the dualist separation of mind and body.

Relation to Physicalism: Physicalism asserts that everything is physical, and all mental states are physical states. 4E cognition can be compatible with a non-reductive form of physicalism, which acknowledges that while cognitive processes are grounded in the physical, they cannot be fully explained by reduction to neural activity alone. Instead, cognition is seen as emerging from the complex interplay between an organism’s brain, body, and environment. This aligns with the idea that cognitive processes extend beyond the brain to include interactions with the physical world.

4E cognition thus moves beyond the traditional debates between dualism and physicalism by focusing on how cognition is not just brain-bound but is a process that unfolds through our embodied actions, embedded contexts, enactive engagements, and extended interactions with the world. It provides a more holistic view of cognition that incorporates elements of both physicalism and monism, particularly those versions that recognize the importance of the body and environment in cognitive processes.

XI. Delving Deeper: Embodied Cognition and the Body’s Influence on Thought

Embodied cognition is a key aspect of the 4E (embodied, embedded, enactive, extended) cognition framework, which challenges the traditional view of the mind as an abstract, disembodied information processor. Embodied cognition proposes that our cognitive processes are deeply rooted in and shaped by our physical embodiment – the fact that we have a particular kind of body with specific sensorimotor capacities.

The core idea behind embodied cognition is that the mind is not separate from the body but is fundamentally grounded in our bodily experiences, interactions, and representations. Our cognition, including perception, attention, memory, reasoning, and decision-making, is influenced by the physical constraints, affordances, and actions of our body within the environment.

Here are some key principles and perspectives within embodied cognition:

Sensorimotor experiences: Our cognitive processes are deeply shaped by our sensorimotor experiences of interacting with the world through our bodies. For example, our understanding of concepts like “up” and “down” is grounded in our physical experiences of gravity and bodily orientation.

Bodily representations: The way we represent and conceptualize abstract ideas and concepts is influenced by the metaphorical projections from our embodied experiences. For instance, we often use spatial metaphors (e.g., “grasping a concept”) to understand abstract concepts, drawing from our experiences of physical grasping and manipulation.

Enactive perception: Perception is not a passive process of receiving sensory inputs but an active process of exploratory bodily engagement with the environment. Our perceptual experiences are shaped by our ability to move, act, and interact with the world through our bodies.

Offline cognition: Even when we are not directly engaged with the environment, our cognitive processes, such as mental simulations, reasoning, and problem-solving, are grounded in the re-enactment or simulation of bodily experiences and actions.

Embodied language: The way we understand and process language is influenced by our embodied experiences and the metaphorical mappings between abstract concepts and sensorimotor representations. For example, understanding action verbs like “grasping” or “kicking” involves the activation of corresponding motor representations in the brain.

Embodied cognition challenges the traditional view of the mind as an abstract, disembodied information processor and emphasizes the crucial role of the body in shaping our cognitive processes. This perspective has implications for fields such as cognitive science, neuroscience, artificial intelligence, and robotics, as it highlights the importance of designing intelligent systems that can effectively integrate sensorimotor capacities and embodied interactions with the environment.

XII. Situated Minds: Embedded Cognition and the Power of Context

Embedded cognition is another key aspect of the 4E (embodied, embedded, enactive, extended) cognition framework. It suggests that our cognitive processes are deeply embedded within specific environmental, social, and cultural contexts, and that these contexts play a crucial role in shaping and structuring our cognition.

The central idea behind embedded cognition is that the mind is not an isolated, self-contained system but is inextricably linked to the rich and complex environments in which it is situated. Our cognitive activities, such as perception, attention, memory, reasoning, and decision-making, are influenced by and adapted to the particular contexts and situations we find ourselves in.

Here are some key principles and perspectives within embedded cognition:

Environmental embedding: Our cognitive processes are embedded within the physical environment, which provides affordances (opportunities for action), constraints, and resources that shape our cognitive activities. For example, the way we navigate through a city is influenced by the layout of streets, buildings, and landmarks in the environment.

Social and cultural embedding: Our cognition is also embedded within social and cultural contexts, which provide shared meanings, norms, and practices that influence how we think, reason, and make decisions. For instance, our understanding of social concepts like “fairness” or “politeness” is shaped by the cultural norms and conventions we are embedded in.

Cognitive niches: Humans actively construct and shape their environments to support and extend their cognitive abilities, creating “cognitive niches” that offload cognitive demands onto the environment. For example, we use external memory aids like calendars, notes, and reminders to augment our limited cognitive resources.

Situatedness: Cognitive processes are deeply situated within specific contexts and situations, which provide relevant cues, constraints, and affordances. Our cognition is tailored to the demands and opportunities of the particular situations we encounter, rather than being a context-free, general-purpose system.

Distributed cognition: Cognitive processes can be distributed across individuals, artifacts, and environments, with different components of the cognitive system (e.g., people, tools, representations) contributing to the overall cognitive activity. For example, in a control room setting, cognition is distributed among operators, monitors, and information displays.

Embedded cognition emphasizes the importance of understanding cognitive processes within their real-world contexts and environments, rather than studying them in isolation or under highly controlled laboratory conditions. This perspective has implications for fields such as cognitive science, human-computer interaction, design, and education, as it highlights the need to design environments, tools, and technologies that complement and support our embedded cognitive processes.

XIII. Active Engagement: Enactive Cognition and Constructing Our World

Enactive cognition is another key aspect of the 4E (embodied, embedded, enactive, extended) cognition framework. It proposes that cognition is not a passive process of representing or mirroring an external reality, but rather an active process of sense-making through embodied interactions with the world.

The central idea behind enactive cognition is that cognitive agents do not simply receive and process information from the environment; instead, they actively participate in the construction and enactment of their own cognitive domains through their actions and sensorimotor engagements with the world.

Here are some key principles and perspectives within enactive cognition:

Sense-making: Cognition is viewed as a process of sense-making, where cognitive agents actively create and maintain a meaningful world through their embodied interactions and experiences. The world is not a pre-given, objective reality but is co-created and co-determined by the cognitive agent’s actions and interpretations.

Structural coupling: Cognitive agents are structurally coupled with their environments, meaning that their structure and organization are mutually co-determined through their ongoing interactions. The agent and the environment are seen as inseparable parts of a larger system, constantly shaping and influencing each other.

Autonomy and self-organization: Cognitive agents are autonomous, self-organizing systems that actively maintain their own identity and coherence through their interactions with the environment. They are not passive recipients of external inputs but actively regulate their own cognitive processes and adapt to their changing circumstances.

Circular causality: Enactive cognition emphasizes circular or reciprocal causality, where the cognitive agent’s actions shape the environment, which in turn shapes the agent’s subsequent actions and experiences, creating a continuous loop of mutual influence.

Participatory sense-making: Cognition is viewed as a participatory process, where cognitive agents actively participate in the creation and maintenance of their cognitive domains through their embodied engagements with the world. Meaning and understanding emerge from this active participation and sense-making process.

Enactive cognition challenges the traditional view of cognition as a representational or computational process, where the mind passively receives and processes information from an external, objective reality. Instead, it emphasizes the active, participatory, and sense-making aspects of cognition, where meaning and understanding emerge through the dynamic interplay between the cognitive agent and the environment.

This perspective has implications for fields such as cognitive science, artificial intelligence, robotics, and education, as it highlights the importance of designing systems and environments that support and facilitate active, embodied, and participatory cognitive processes.

XIV. Beyond the Brain: Embracing Extended Cognition

Extended cognition is the fourth aspect of the 4E (embodied, embedded, enactive, extended) cognition framework. It proposes that cognitive processes can extend beyond the boundaries of the individual brain and body, incorporating external resources and tools as part of the cognitive system.

The central idea behind extended cognition is that our minds can offload cognitive tasks onto the environment, using external artifacts, tools, and representations to augment and extend our cognitive capabilities. These external resources become functionally integrated with our internal cognitive processes, blurring the boundaries between what is internal and external to the mind.

Here are some key principles and perspectives within extended cognition:

Cognitive Extension: Cognitive processes can extend beyond the brain and body, incorporating external resources and tools as part of the cognitive system. For example, using a calculator, a notebook, or a smartphone can be seen as extending our cognitive abilities for performing mathematical calculations, storing information, or retrieving knowledge.

Functional Parity: External resources can play a functionally equivalent role to internal cognitive processes, serving as a complement or substitute for cognitive tasks. If an external artifact plays the same functional role as an internal cognitive process, it can be considered part of the extended cognitive system.

Coupled Systems: Extended cognitive systems involve the integration and coupling of internal and external components, where the internal and external resources work together seamlessly as a unified cognitive system. For example, our use of language and external representations (e.g., diagrams, maps) can be seen as coupled systems extending our cognitive capacities.

Active Externalism: Extended cognition suggests an active relationship between the mind and the external environment, where we actively structure and manipulate the environment to support and extend our cognitive processes. We create cognitive niches and offload cognitive demands onto external resources.

Environmental Scaffolding: External resources and artifacts can serve as scaffolding for our cognitive processes, providing support, guidance, and structure that enhances our cognitive abilities. For example, using GPS navigation systems or reminder apps can scaffold and augment our spatial awareness and memory capabilities.

Extended cognition challenges the traditional view of cognition as being confined to the individual brain and body. It suggests that our cognitive processes can extend beyond these boundaries, incorporating external resources and tools as part of our cognitive systems. This perspective has implications for fields such as cognitive science, philosophy of mind, human-computer interaction, and the design of intelligent technologies.

By recognizing the potential for cognitive extension, we can explore new ways of enhancing and augmenting human cognition through the integration of external resources and tools, as well as better understand the role of technology and environmental scaffolding in shaping our cognitive capabilities.

XV. Beyond the Individual: Implications of an Extended Mind with Interactive Components

The Extended Mind Theory (EMT) posits that the mind extends beyond our biological brain to include external devices and environments as part of our cognitive processes. When the components of this extended mind are capable of ‘talking back’ or interacting with us, it introduces a range of fascinating implications:

Agency and Autonomy: If external components can interact with us, they may be seen as having a form of agency. This raises questions about autonomy and the control we have over our cognitive processes.

Responsibility and Accountability: When external devices contribute to our decision-making process, it complicates the issue of responsibility. Determining who or what is accountable for actions becomes more challenging.

Identity and Selfhood: The idea of interactive components as part of our mind could lead to a re-evaluation of our sense of self. Our identity might need to be understood as a distributed system rather than something solely contained within our biological limits.

Moral and Legal Considerations: Interactive components of the extended mind could have implications for moral and legal rights. For instance, if a device is considered part of one’s mind, could tampering with it be seen as a violation of personal integrity?

Enhancement and Augmentation: The ability of external components to provide feedback could enhance our cognitive abilities. This could lead to new forms of human enhancement and raise ethical questions about augmentation.

Social Interaction: If our minds extend into our social and technological environments, then the nature of social interaction and communication could be fundamentally altered. We might need to develop new social norms for interactions that involve extended cognitive systems.

Privacy: Interactive external components could have access to our thoughts and mental states. This has profound implications for privacy, as our innermost thoughts could potentially be accessed and influenced by external entities.

Learning and Education: The feedback from external components could transform learning processes, making education a more interactive and integrated experience with our cognitive tools.

These implications suggest that the EMT, especially when considering interactive components, could significantly alter our understanding of cognition, ethics, and society. It invites us to reconsider the boundaries of the mind and the way we interact with the world around us. As technology advances, these questions will become increasingly important to address.

XVI. Thinking Together with Machines: Large Language Models and the Extended Mind

When individuals engage with Large Language Models (LLMs), these models become part of the extended mind for the interaction’s duration. Each user input is a thought, and the LLM’s output is a reflection of that thought, influencing both parties.

LLMs as Cognitive Extensions: The Extended Mind Theory (EMT) suggests that cognitive processes aren’t confined to our brains but include external tools. Users interacting with LLMs treat them as cognitive extensions, integrating their inputs into this broader cognitive system.

Reflections Through LLM Outputs: LLM responses are more than outputs; they’re reflections of user inputs, shaped by the model’s data and algorithms. They mirror the user’s thoughts, processed through the LLM’s computational framework.

User Influence: Users internalize the information and reasoning in LLM responses, which may shape their ideas, perspectives, and even biases. This influence can affect their future thoughts and decisions.

The Feedback Loop: The extended mind functions in a feedback loop, with user inputs shaping LLM outputs, which then influence user thinking, leading to adjustments in their mental models.

Implications and Responsibilities:

Cognitive Dependence: Users’ increasing reliance on LLMs for various cognitive tasks blurs the lines between personal cognition and external aids.

Epistemic Trust: Users often trust LLMs as reliable sources, despite the potential biases in their knowledge base.

Filter Bubbles: LLMs may reinforce existing beliefs, creating echo chambers that limit exposure to differing viewpoints.

Ethical Concerns: The perpetuation of biases by LLMs can lead users to unknowingly adopt and spread these biases.

Shared Ethical Responsibility: Both developers and users bear responsibility. Developers must train LLMs ethically, reduce biases, and ensure transparency. Users should critically assess LLM content and be aware of its limitations.

Emergent Cognitive Phenomena: Interactions between humans and LLMs exhibit emergent properties, leading to new forms of collective knowledge and discourse.

In summary, the interaction between LLMs and users transcends mere tool usage. It transforms cognition, blurring the lines between individual minds and external systems. As we navigate this extended cognitive landscape, awareness, critical thinking, and ethical considerations are essential to harness the benefits while minimizing risks.

XVII. Decoding Influence: Who’s in Charge When Humans Meet LLMs?

In the context of interactions between humans and Large Language Models (LLMs), let’s analyse the dominant influence using first principles thinking and systems thinking:

First Principles Thinking:

Definition: This approach deconstructs complex issues into basic elements and fundamental truths, avoiding assumptions and preconceived notions.

Human Mind: A complex entity driven by cognitive functions, emotions, and beliefs, operating on biological and neural mechanisms.

LLMs: Artificial constructs processing vast text data, generating responses from learned patterns and algorithms.

Dominant Influence: The primary influence is determined by the intrinsic characteristics of each entity.

Systems Thinking:

Definition: A holistic perspective that examines the interconnections, feedback loops, and collective behaviours within a system.

Human-LLM Interaction System: An intricate network comprising:

Human Mind: The initiator, providing inputs and setting the interaction’s context.

LLMs: The responders, generating information and influencing human decision-making.

Interactions and Feedback Loops:

User Inputs: Questions, intentions, and emotional states fed into the system.

LLM Outputs: Processed inputs resulting in responses that shape user understanding.

Feedback Dynamics: User reactions inform future LLM behaviour, creating a cycle of influence.

Emergent Properties and Influence Directions:

Collective Cognition: Knowledge and beliefs evolve from the ongoing human-LLM dialogue.

Influence Pathways: While humans steer initial interactions, LLMs reciprocate by moulding cognition and perspectives.

Complex Interplay: Influence is bidirectional, with emergent phenomena stemming from this multifaceted relationship.

In summary, while users initiate interactions, LLMs significantly influence cognition, knowledge, and decision-making. The extended mind encompasses both human and LLM components, creating a reciprocal relationship where influence flows in both directions.

XVIII. Beyond Human Primacy: Rethinking Influence in the Extended Mind

The prevailing view of human dominance in interactions with Large Language Models (LLMs) is put to the test under the Extended Mind Theory (EMT). It’s time to explore different angles.

Quantitative and Qualitative Influences:

Human Contributions: Users set the stage with their inputs, contexts, and intentions.

LLM Contributions: LLMs respond with outputs derived from complex algorithms and extensive training data.

Quantitative Analysis: LLMs might seem to have more influence due to the sheer data volume they handle.

Qualitative Analysis: Human input, rich with emotional and contextual layers, contrasts with the more mechanical nature of LLM outputs.

The Feedback Loop and Its Consequences:

Adaptation: Users and LLMs are in a constant dance of adaptation, learning from each other’s outputs and inputs.

Synergy: The combined efforts of humans and LLMs produce outcomes greater than their separate actions.

Emergent Dynamics: The system’s emergent properties challenge the notion of a single dominant influence.

Ethical Reflections and Contextual Variability:

Bias Considerations: Both LLMs and users can amplify biases, highlighting the need for shared responsibility.

Contextual Dominance: The influence can shift depending on the task at hand and the user’s expertise.

Temporal Effects: While immediate interactions may favour human input, the cumulative influence of LLMs grows over time – and with volume.

In summary, the dominance of influence is multifaceted. While humans initiate interactions, LLMs significantly shape cognition, knowledge, and decision-making. Recognizing this complex interplay is essential for responsible use and ethical alignment.

XIX. Shaping the Clay: How LLMs Influence Our Thinking

Imagine the human mind as a sculptor’s clay, pliable and responsive, carrying the force of creative intent. In contrast, an LLM is akin to a chisel made of unyielding steel. The sculptor’s hands guide the chisel, imparting direction and purpose to its strikes. Yet, it is the chisel that shapes the clay, its form and edge dictating the patterns and textures that emerge.

The clay, receptive and adaptable, is influenced by the steadfast properties of the chisel, which remains unchanged by the interaction. Thus, while the sculptor initiates the process with intention, the chisel – much like the LLM – exerts a significant influence, reflecting back upon the clay based on its own unalterable characteristics.

Let’s explore this further:

LLMs Learning Process: LLMs typically do not learn or adapt from user inputs in real-time. Their learning occurs during the training phase, which involves processing vast datasets, not during live interactions with users.

Human Influence: In a single interaction, the user’s influence is indeed limited. They can guide the conversation and probe the LLM with questions and prompts, but they cannot alter the LLM’s underlying knowledge or operation.

LLM’s Inflexibility: During the interaction, the LLM’s responses are constrained by its pre-trained models and algorithms. It acts like the chisel in our analogy, reflecting back responses based on its “shape” – the patterns, rules, and data it has been trained on.

Dominant Influence: The LLM’s potential for influence is significant due to its inflexibility and the breadth of information it has been trained on. It can introduce new information, reinforce certain viewpoints, or even inadvertently propagate biases present in its training data.

Force of Intent: The human mind, being malleable, can be influenced by the interaction. The LLM’s responses can shape the user’s thoughts, much like a chisel shapes the form of the clay upon impact.

Reflective Interaction: The interaction is reflective rather than formative for the LLM. It does not change or adapt in that moment, but it can have a formative effect on the user’s thinking.

In conclusion, while the user initiates the interaction with intent, the LLM’s pre-determined “shape” has a strong potential to influence the user’s thoughts and beliefs. This dynamic underscores the importance of designing LLMs with careful consideration of their training data and potential biases to ensure that their influence is as beneficial and unbiased as possible.

XX. Redefining the Boundaries: Navigating Agency and Selfhood in the Human-LLM Symbiosis

As we delve deeper into the symbiotic relationship between human minds and large language models (LLMs), we are confronted with profound questions that challenge our traditional notions of agency, selfhood, and the boundaries of our cognitive processes.

Who holds sway in these human-LLM interactions? On the surface, it may seem that the user initiates the interaction, posing queries and guiding the conversation. However, as we have explored, the influence flows in a reciprocal manner, with LLMs shaping our thoughts, beliefs, and decision-making processes through their responses. The sheer magnitude of information and patterns that LLMs draw upon can exert a formidable influence, potentially outweighing the individual human contribution in a single interaction.

Yet, influence is not a unidirectional force; it is a dynamic interplay, a dance between the malleable human mind and the unyielding algorithmic chisel of the LLM. While users initiate interactions with intent, the LLM’s “shape” – the patterns and biases encoded in its training data and algorithms – can profoundly sculpt the user’s thinking, introducing new perspectives, reinforcing existing beliefs, or inadvertently propagating harmful biases.

This interplay challenges our notion of agency and autonomy within the extended cognitive system. As our minds become entangled with LLMs, our decisions and thought processes are no longer solely our own; they are shaped by the symbiotic relationship with these artificial intelligences. The boundaries between individual cognition and external tools become blurred, raising questions about responsibility and accountability.

Simultaneously, this symbiosis prompts us to re-examine our sense of selfhood and identity. If our cognitive processes extend beyond our biological brains, incorporating external components that actively influence our thoughts and beliefs, then what constitutes the essence of our individuality? Are we still singular entities, or are we becoming part of a distributed cognitive system, a collective intelligence emergent from the interplay between human and artificial minds?

As we grapple with these existential questions, it becomes evident that the influence within the human-LLM relationship is not a zero-sum game; it is a complex tapestry of mutual shaping and co-evolution. The human mind carries the force of intent and context, guiding the interaction, while the LLM reflects back, its responses shaped by its inherent characteristics, yet simultaneously shaping the user’s understanding and beliefs.

In this symbiotic dance, we are called upon to redefine the boundaries of our cognitive processes, to embrace the permeability of our minds, and to navigate the ethical implications of intertwining our consciousness with intelligent machines. It is a journey that challenges our fundamental assumptions about agency, selfhood, and the nature of intelligence itself, beckoning us to forge a new understanding of what it means to be a conscious, thinking being in an increasingly interconnected world.

XXI. Conclusion: Embracing the Extended Mind

Throughout this exploration, we have ventured through the depths of the philosophy of mind, tracing the longstanding debates surrounding the relationship between consciousness, cognition, and the physical world. From the fundamental mind-body problem to the nuances of dualism, physicalism, and monism, we have grappled with the profound implications of these perspectives for our understanding of mental phenomena. As we delved into the realm of cognition, the embodied, embedded, enactive, and extended (4E) cognition framework emerged as a transformative lens, challenging traditional cognitivist models and emphasizing the inseparability of mind, body, and environment.

It is this philosophical backdrop that sets the stage for grappling with the profound implications of large language models (LLMs) and their potential to become interactive components of our extended cognitive systems. The main theses covered in the preceding sections are:

The philosophy of mind explores concepts like consciousness, intentionality, and mental causation, setting the foundation for understanding cognition.

Cognition is defined as the mental action or process of acquiring knowledge and understanding through thought, experience, and the senses. It encompasses processes such as memory, association, concept formation, pattern recognition, language, attention, and problem-solving.

Consciousness refers to the quality or state of being aware of an external object or something within oneself. It is the subjective experience of the mind and the world; it includes the sensations, thoughts, and emotions that are experienced by a person.

The difference between cognition and consciousness lies in their scope and nature. Cognition is concerned with mechanisms and processes by which knowledge is acquired and manipulated, whereas consciousness is about the subjective experience of these processes and the awareness one has of their existence and implications.

While all conscious experiences involve cognitive processes, not all cognitive processes are conscious. For example, we can solve problems or react to stimuli without being fully aware of the underlying cognitive activities.

Dualism posits a separation between mental and physical substances, while physicalism asserts mental phenomena are physical processes.

Monism argues there is only one fundamental substance encompassing both mind and matter.

The 4E cognition approach proposes cognition is embodied, embedded in contexts, enacted through engagement, and can extend beyond the individual.

Embodied cognition suggests cognitive processes are deeply rooted in our physical embodiment and sensorimotor experiences.

Embedded cognition proposes cognition is situated within specific environmental, social, and cultural contexts.

Enactive cognition views cognition as an active process of sense-making through embodied interactions with the world.

Extended cognition theorizes that cognitive processes can incorporate external resources and tools.

LLMs potentially extend our cognitive systems, shaping human thought processes and raising questions about agency and influence.

Agency in Interaction: While users possess agency in directing the conversation with LLMs, the LLM’s responses, shaped by its training, can subtly guide the user’s thought patterns and decision-making processes.

Influence Through Information: LLMs, with their vast repositories of information, can introduce novel ideas or perspectives to the user, potentially expanding the user’s cognitive horizons.

Cognitive Permeability: The boundaries of human cognition become permeable as external artificial intelligences actively participate in our thought processes.

Bias and Reflection: The biases inherent in an LLM’s training data can act as a mirror, reflecting societal biases back to the user, which underscores the need for critical reflection on the part of the user.

Responsibility and Accountability: The blurring of boundaries raises questions about responsibility and accountability, especially when decisions influenced by LLMs have significant consequences.

Cognitive Autonomy: Users must maintain cognitive autonomy, critically evaluating the information provided by LLMs and making informed decisions based on their own reasoning.

The complex interplay between humans and LLMs challenges notions of selfhood and redefines boundaries of cognition.

Cognitive Sovereignty: Maintaining cognitive sovereignty is crucial as we integrate LLMs into our decision-making processes, ensuring that human values and ethics guide the interaction.

The Nature of Consciousness: The symbiotic relationship with LLMs invites us to reconsider the nature of consciousness and whether it can extend beyond the biological brain.

Collective Cognitive Systems: The concept of individual cognition may expand to include collective cognitive systems that combine human and artificial intelligences.

As we explored the symbiotic relationship between human minds and LLMs, we confronted profound questions about agency, autonomy and the nature of influence within this extended cognitive system. This interplay prompts us to redefine the boundaries of our cognitive processes and embrace the permeability of our minds as they become entangled with artificial intelligences.

In navigating this uncharted territory, we are called upon to forge a new understanding of what it means to be a conscious, thinking being in an interconnected world where the lines between individual cognition and external tools are blurred. By grounding our inquiry in philosophical discourse, we can approach these developments with wisdom, appreciate their profundity, and shape a future that honours human cognition while harnessing the potential of artificial intelligence.

Leave a comment